TROIKA: Russia's Oreshnik and the Future of Strategic-Level Weapons

Russia uses its 'unbeatable' hypersonic missile capabilities to intimidate and threaten the West. But is this nuclear blackmail credible, or an empty threat?

In 1842’s Dead Souls, Nikolai Gogol compared the out-of-control Russian Empire to the troika, a fast-traveling sled pulled by three horses.

“The flying road turns into smoke,” Gogol writes, “...for you are overtaking the whole world, and shall… force all nations to give you way.”

One hears echoes of Gogol’s troika in Vladimir Putin’s brutal demonstrations of the Oreshnik, a next-generation hypersonic weapon. The Oreshnik rocket (Орешник: hazel shrub, for the tree of smoke produced by launch) is renowned for its speed and agility, which supposedly allows it to surpass and outmaneuver even the most advanced air defense systems. Like the troika, it represents a nation out of control, obsessed with revanchist notions of lost empire. But it is perhaps most powerful as a psychological weapon.

Each time Russia deploys it against Ukrainian infrastructure, it represents a powerful threat to Western powers, as we have so far failed to intercept or shoot down the Oreshnik. It travels at Mach 10: 8,000 miles per hour, ten times the speed of sound. In the later stages of a strike, when air defense would usually be critical, this weapon is simply too fast to defend against. Unlike the more expensive and risky hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) prototypes, the Oreshnik achieves hypersonic speeds through rapid ballistic descent, not sustained atmospheric glide. It maneuvers as it travels; it can make microscopic adjustments in-flight. It can potentially carry up to thirty-six nuclear munitions, allowing Russia to render wide swaths of battlefield uninhabitable for decades or empowering decapitation strikes against a state’s entire command structure. For the first time since the introduction of the Patriot system, Russia can hit us where they want, when they want.

At least, that’s what they want us to think. This is the maximal intimidation narrative. The Oreshnik’s existence is atomic blackmail; it implies a coming nuclear war. Its use is simple power posturing. In this regard it is not unlike the Soviet Union’s record-setting 50-megaton Tsar Bomba test, conducted in 1961.

The Shot(s) Heard ‘Round the World

The Oreshnik has been deployed twice in the past fourteen months. It was first launched in November of 2024, against Dnipro, Ukraine’s fourth-largest city. The Oreshnik was launched from a base in Southwestern Russia; it quickly climbed past the sky and slipped into the upper atmosphere. The extreme thinness of the atmosphere reduced the air resistance on the rocket, and it shot silently over the horizon, invisible to Ukraine’s web of American-made air defense systems. Then its direction changed: it began to fly downwards. The increasing force of gravity compounded its speed. Just minutes after launch and mere seconds to impact, it reached speeds more than seven times the speed of sound. As the rocket entered the lower atmosphere, its nose broke away, revealing six MIRVs (multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles). The munitions dropped from the body of the rocket and activated their own propulsion systems, followed milliseconds later by brilliant, electric-white flashes. On the ground, it would have looked like a massive, spontaneous electric storm as the munitions screamed down and evaporated their targets, one after another after another. The strike reduced a massive Soviet-era aerospace depot to rubble.

According to senior Ukrainian officials, the munitions used in the strike were non-explosive, non-nuclear ‘dummies.’ The destructive power of the strike was derived simply from the monumental speed at which the missile travels. The six vehicles, however, are designed to carry six nuclear warheads each. If the Oreshnik had been armed, Dnipro’s 968,502 citizens would have had a few seconds’ warning before being struck by thirty-six nuclear bombs.

The second strike was eleven days ago, on the city of Lviv, the fifth-largest in Ukraine. It began with a massive barrage of Iranian-made Shahed drones, which struck electrical transformers, power stations, coal-fired power plants, and pipelines. Then the Oreshnik entered the lower atmosphere at Mach 11. Its reentry vehicles arced white across the night sky before striking an “undisclosed facility.” One potential target is the Bilche-Volytsko-Uherske Underground Gas Storage Facility, the largest of its kind in all of Europe.

Minutes before the 2024 strike, Russia notified the United States through nuclear risk reduction channels, but no such notification was provided in the 2026 strike. But perhaps that’s by design. The Foundation for the Defense of Democracies writes:

“In a war with NATO, Russia could employ [Oreshniks] for prompt deep strikes on high-value area targets such as aircraft parked at air bases. However, using such an expensive missile for a routine attack on Ukrainian infrastructure, when Russia has cheaper and more abundant munitions better suited for that purpose, makes far less military sense… the Russians likely intended more for a psychological rather than military effect.”

The strike killed a family of four. Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians were left without power, which rapid response teams are still working to restore. Putin’s hypersonic saber-rattling is not just a threat to the West, but a campaign of total war designed to break the resolve of Ukrainians, who show no signs of giving up.

Beyond Deterrence: The Forensic Evidence

In Gogol’s description of the troika, he alludes to the psychological effect on those who witness this speeding bullet of history:

“…the spectators, struck with portent, halting to wonder you be not a thunderbolt launched from heaven? What does that awe-inspiring progress of yours foretell? What is the unknown force which lies within your mysterious steads?”

But this is just what Putin wants from us. We must move past fear, past dumbfoundedness, past outrage at yet another violation of the taboo against intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), and instead analyze the evidence left behind by the first field-tests of this weapon.

Exhibits I & II: Entry Vehicles Separate

The two videos1 below were recorded by CCTV cameras just south of Lviv on the 8th of January, 2026.

Open on houses and parked cars; the fence and snow-covered hood visible in the bottom-center of exhibit I is visible in the bottom-left of exhibit II. In both cases, there is first a brilliant orange flash in the sky, visible in the top-right corner. This first flash is most likely the incredible heat of the nose separating from the hypersonic rocket, disgorging the six MIRVs. The six light objects, which resemble ridged cylindrical flashes, are the afterimage of these vehicles falling to earth. They fire in succession, almost like a six-shooter revolver.

This lag-time may provide a small window of opportunity for extremely advanced air defense systems like the American THAAD. Much more promising is the potential for a drone-based response, though such a defense system would require a web of drones in the air for the entire duration of a potential strike.

Exhibit III: Impact

The footage2 below was taken from an undisclosed camera, some miles from the other videos. This camera was much, much closer to the strike, providing a clearer view of the reentry vehicles as they strike their targets.

Open on a view of the sky with trees in the lower third of the frame. This appears to be a more rural area, outside Lviv proper. First is the luminous flash visible in the other videos. This is high-speed lower-atmospheric entry; the MIRVs are breaking away. Then, at about 0.9 seconds, a bright, luminous streak descends diagonally. This is the first of the MIRVs. Near the end of the second 1, there is a single frame of separated dummy warheads, also known as flechettes. If the Oreshnik was nuclear-armed, these would be the warheads. They strike the ground just over the horizon of the video. At around 3 seconds the camera begins to shake, and by 10 seconds the attack is mostly over, though residual flashes continue. It’s possible that these flashes represent ground explosions, ammunition cook-offs, or large-scale oil and natural gas combustion. Between the late 2024 strike and the early 2026 strike, one thing remains clear: that energy targets have been prioritized. But why?

Why Now?

We’ve developed three hypotheses that may explain why the Oreshnik was deployed at these particular times. As a primer, consider the two attacks in the context of the aggregate strikes on Ukraine.

Hypothesis I: Drawdown Prevention

It’s possible that Oreshnik launches are ordered by generals during concerns about potential Russian military drawdowns.

Late 2024 was particularly punishing for Russian forces, with Ukraine accessing new weapons systems. Taiwan transferred its stock of retired Hawk missiles to Kyiv. Ukraine fired the British-made Storm Shadow for the first time. Biden authorized an ATACMS strike inside Russia for the first time. And, perhaps most relevantly, Trump was elected on November 5th. His (ultimately hollow) promises to promptly end the war in Ukraine may have made Russian military leaders more interested in assertiveness and power-posturing.

However, this hypothesis is less effective when applied to the early 2026 strike. Apart from the possibility of internal strife, the Russian military appears far from a drawdown. Rather, if nothing changes, they’re poised to gain substantial territory in the coming weeks. Zelenskyy warned today that Russia is preparing to mount a major attack, beginning with the destruction of power grids.

Hypothesis II: Winter War

It’s also possible that Oreshnik launches are ordered by generals directly before major weather events. Freezing cold temperatures (which can prove disruptive to Eastern European cities even in the best of times) become much more dangerous with broken power grids. If the Ukrainian state is left shivering in the dark, this theory holds, defeating them becomes much simpler. Therefore, Russia strikes them in late 2024, as that year’s winter deepens, and again in early 2026, just as this year’s winter hits its zenith.

The problem with this hypothesis is that this winter war is not particularly effective. Power crews work tirelessly to restore the grid; they are 58,000 in number and their ranks are only growing. The Institute for the Study of War reports that Russia’s attacks on the grid may begin to target nuclear power plants; this is a clear sign of desperation, a last-ditch attempt to supplant a failing strategy. But most of all, the bombardment of energy facilities has not weakened the resolve of everyday Ukrainians. Rather, it has galvanized the country, uniting them against Russian aggression and inspiring them to stay the course until peace is won.

Hypothesis III: Tsar Putin

Finally, it’s possible that the Oreshnik launches are militarily incoherent, and ordered by Putin, motivated by his whims. This hypothesis considers the 2024 strike a message by Putin to Trump as a demonstration of Russian power before he takes office. The 2026 strike, then, must be Putin’s response to the ‘drone attack’ on his Novgorod dacha. However, American analysts (and Trump) do not believe that any such attack occurred.

Ultimately, neither statistics nor weather nor personalism can provide a compelling explanation of the Oreshnik’s use. It may not be possible to determine when the next strike will come, but perhaps we can identify where it will come from.

Dead Souls (I): The Belarusian Threat

On December 30, the Russian and Belarusian defense ministries announced that a Russian Strategic Missile Forces battalion equipped with Oreshniks had begun combat duty in Belarus, apparently at a site near the Russian border. The footage they released, however, showed only auxiliary vehicles, not the launchers, and the site is apparently not yet complete. This narrows down the work significantly: a few candidate sites in Belarus would be enough to develop a rough idea of where the Oreshnik might be stationed. With a site in mind, we can begin to calculate what threat it truly poses to NATO and Western Europe.

I’ve identified four sites that fit this definition: the 465th Missile Brigade in Asipovichy, the Krichev-6 Aerodrome in Krychaw, a Soviet-era strategic missile base in Paulauka, and the Zyabrovka Airfield in Zyabrovka.

Site I: Krichev-6

History repeats itself at Krichev-6 in Eastern Belarus, closer to the country’s Russian border than its Ukrainian one. Boris Yeltsin asked that this site be destroyed, according to Military Watch Magazine, as it was a relic of Moscow’s nuclear program in Belarusian territory. This winter, Middlebury College argued that this site had been revived to host the Oreshnik.

This is short of perfectly compelling, though. Their own article notes that Belarus’s Aleksandr Lukashenko said the Oreshnik was not deployed at Krichev-6, but “somewhere more advantageous, but I will not speak about that.”

This leaves us to consider the definition of “advantageous,” and forces us to explore sites further South than Krichev-6, sites closer to Kyiv and Lviv.

Sites II & III: Paulauka and Zyabrovka

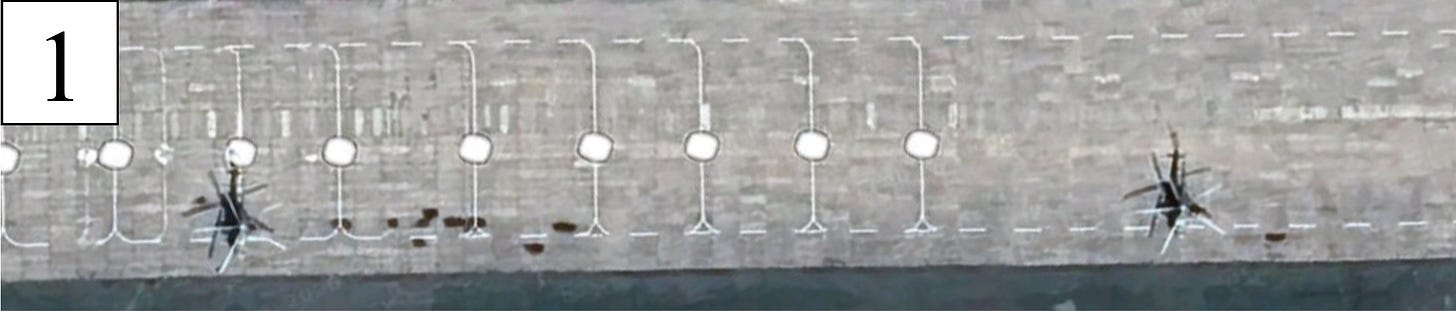

These next candidate sites are twins. They both clear the bar for “advantageousness,” but also carry trade-offs and irregularities. When compared to Krichev-6, Paulauka and Zyabrovka are about 50% and 75% closer to Kyiv respectively. Exhibit 1 is the airfield at Zyabrovka; Exhibit 2 is the new construction at Paulauka.

However, I’ve determined that the viability of each site is substantially complicated by geography and development.

The airfield at Zyabrovka (Exhibit 1) is in disuse and disarray. There’s no publicly accessible evidence of contemporaneous military presence. The area around the tarmac has been denuded; little to no tree cover remains. This erases any chance of hiding the Oreshnik or its launch equipment. All told, as launch sites go, it’s possible, albeit improbable.

The construction site at Paulauka (Exhibit 2) is a different story. Ample tree cover exists to hide the weapons system, but the roads are light earth, inconsistently paved, with sharp turns and little concrete foundation. Furthermore, the square-shaped plots lack a connecting tarmac, meaning that the site lacks air accessibility. Even if construction has rapidly progressed since these satellite images were taken, this is another potential but improbable site.

There is, however, a fourth candidate.

Site IV: Asipovichy

Out past Minsk, the territory starts to militarize. The road grade flattens and the highways widen; they’re made to accommodate tanks, supply trucks, and heavy weapons, traveling cross-country to small outposts and supply stations. Asipovichy, the site of the Belarusian 465th Missile Brigade, is one such outpost.

Ukrainska Pravda writes that Radio Liberty satellite analysts identified major construction at Asipovichy. The construction shows clear signs of both military activity and reinforcements consistent with missile infrastructure.

This is Asipovichy. It consists of a long concrete runway with multiple taxiways, nestled in a forested area just Southeast of Minsk. Since the beginning of the Russian invasion in 2022, it has been regarded as a rear-area base: a hub for the transit of food, materiel, and the injured and dead. Today, it is being transformed by a twenty-million dollar renovation. Note the three areas of interest below:

These are wide-body helicopters. The five-rotor pattern and two-finned tails distinguish them as Mi-8s or Mi-17s. The small oil stains visible on the tarmac clearly indicate regular use: these are utility helicopters, shuttling people and supplies to and from the airfield. But with no major force buildup at the base and no other vehicles visible, what purpose do these utility helicopters serve? The answer is simple: construction.

This is a support compound for a group of aircraft or a complex weapons system, but it’s not finished. What you are seeing is a grid of narrow roads with multiple small ‘cutouts’ tucked into natural tree cover. These are hardstands, designed to protect and hide trucks, fuel tanks, or air defense batteries. Think of them as open-air garages for important resources. The scarred, light-brown earth in the bottom-center of this photo betrays the site’s incompleteness, along with the lack of cover in the bottom right corner. If one reads this image like a clock, starting at ‘midnight,’ the ‘hours’ from one o’clock to three o’clock are barren; construction intensifies at four. By eleven o’clock, we find completed hardstands, possibly protecting Ural-4320 supply trucks.

If this site is indeed being retrofitted for the Oreshnik, these hardstands are built to hide and protect the transporter erector launcher (TEL) vehicle, the missile itself, and the targeting systems which guide it on its flight. Such a missile cannot be launched from a hardstand, however. This is where the next image comes in.

The center of the construction activity at Asipovichy is here, just off the main tarmac. The ground has been utterly leveled, revealing light-colored earth on both sides of the road. But there are also areas with mixed tones and irregular churn. This is not neatly graded, one-time construction. Rather, we’re seeing frequent and continuing traffic by construction vehicles. The roads are telling too: it’s wider than most of the roads on the airbase and its corners are longer and gentler. This provides long, heavy TEL vehicles the space they need to turn, maneuver, and navigate.

Most critically, there’s a rectangular structure with two large earthwork berms at the center of the construction site. This kind of enclosure is anomalous. It doesn’t match the other hardstands and is not consistent with helicopter storage units. It’s too widely-spaced to be weather protection, with two wide openings at either end. This is a site for a high-value vehicle like a TEL, and the small concrete rectangles scattered around the site are well-suited for communications equipment, generators, or fuel tanks.

I am moderately confident that this earthwork berm is designed for missile launches, and, if finished, would allow for the deployment of the Oreshnik hypersonic missile.

Dead Souls (II): Back-of-the-Envelope

If the Oreshnik is about to be secreted away south of Minsk, if this site really is being designed to accommodate it, does this spell disaster for European security? Does this foretell a return to fallout shelters and duck-and-cover drills? Is EU support to Ukraine, and indeed the entire NATO deterrence system, about to evaporate?

In answering that question, we must flip the metaphorical envelope over and engage in some back-of-the-envelope math.

First, a key principle: while hypersonic velocity represents a brave new world in defense, it does not repeal physics. The same laws which govern conventional missiles also apply here.

Even at extreme speeds, this missile’s real combat range is its theoretical flight distance reduced by five key factors:

The mass of the payload (the heavier the payload, the more velocity is reduced),

The optimal combat trajectory (in this case, a depressed trajectory designed to complicate interception),

The energy spent deploying, directing, and maneuvering the reentry vehicles (which grows with the number of reentry vehicles),

The accuracy constraint imposed by the Circular Error Probable (CEP) metric,

And the ‘margin of error’ which all launch plans include.

Russian media reports claim the Oreshnik has enough fuel to strike at targets 3,000 to 3,300 miles away from its launch site. But as the above math demonstrates, this is a best-case scenario, far from reality. Three thousand miles is an idealized flight distance assuming optimal trajectory, perfect deployment, full payload survival, and loose requirements for accuracy or reliability. An intercontinental strike imposes all of those constraints harshly and simultaneously. Furthermore, at terminal velocities on the order of Mach 11, even the tiniest structural or thermal margins matter. Quite simply, to argue that the Oreshnik could circumnavigate half of the globe and then penetrate American air defenses is fearmongering. To allow fear of the Oreshnik to influence our policymaking or weaken our support of Ukraine is absurdity.

But what targets would we be remiss not to consider?

If Russia seeks to strike a barely-defended suburb or an open field, the Oreshnik is less sensitive to accuracy and dispersion. These are extremely wide targets: submunitions that land tens or even hundreds of meters apart may still produce militarily meaningful effects. These targets are usually not covered by air defense systems, or the systems are otherwise occupied with drones or taken offline by electronic warfare. Even then, the effective range is far from Russia’s 3,000 mile threat.

For targets like these, experts argue for an effective range of between 1,100 and 1,860 miles.

At this stage of the war, though, few targets fit this definition. Ukrainian air defense shows no signs of giving up, and their counter-drone capabilities grow with each passing day.

For defended point targets, like cities or military installations with strong air defense networks, the range reductions only grow. Unguided dispersion, reentry attrition, and conservative planning assumptions all compound.

For targets like these, argue for an effective range of between 620 and 990 miles. Suddenly, the hypersonic troika of Russian empire is revealed as an exaggeration. Far from a war-ending weapon or a revolution in military affairs, the Oreshnik is, at heart, a mildly more effective ICBM.

Dead Souls (III): The Shadow Over (Central) Europe

This all begs the question: if not London or Paris, if not Washington D.C. or New York, who is truly living in the shadow of the Oreshnik? The answer is simple: Central Europe.

Of mild concern is an Oreshnik strike on a major Central European or Baltic city. Berlin and Warsaw are both well within range, as are Tallinn, Riga, and Vilnius. But with NATO’s Article V collective security pact in effect, the chances of such a strike are slim to none.

Of higher concern is an Oreshnik strike on a major military installation in Central Europe. NATO Allied Air Command at Ramstein Air Base and the USAF 31st Fighter Wing at Aviano Air Base both fall within this range assessment. Even with American air defenses fully functioning, a few submunitions could slip through. Even two or three would be enough to do substantial damage against our rapid-response aircraft, or kill the decision-makers who lead NATO’s air capabilities. But, again, as long as Article V remains in effect, the risks are low.

Of gravest concern are Ukrainian cities, factories, and power infrastructure. The Oreshnik will be most effective here, particularly if coupled with drone swarms to occupy air defense. Our media outlets have written and spoken about this weapon as if it were a threat to Americans, with range stretching from Alaska to Boston and beyond; all the while, defense contractors have overpromised and underdelivered on American hypersonics. But for Ukrainians, the Oreshnik is not a media event, and it is not an opportunity to win a contract. It is, like the war at large, a terrible scourge on their lives. And until we have a stronger understanding of this weapon and how it works, there’s little we can do to keep them safe.

The (Non-)Triumph of the Troika

Both Ukraine and Russia claim Nikolai Gogol; his legacy is contested. The war has transformed that contest, and made it absurd. But his question to the speeding troika remains.

“Where, then, are you speeding, O Russia… whither? Answer me!”

Where is Russia going? What will become of it when this war is over? And what of its war economy, its burgeoning stockpile of hypersonic weapons?

“But there is never any answer — there is only the terrible sound of your bells.”

Yes, Mister Gogol, with that I would have to agree.

For information about the original sources of these videos, please send me an email.

See above.