Martyr: The Secret Lives of Iranian Drones

The IRGC designs drones in Tehran, tests them in Deir ez-Zur, and ships them across the Caspian, to rain fire on Kyiv. What’s the point of it all?

In a globalized world, weapons have secret lives. Stamped as “spare parts” or “tractor equipment,” they move through distant ports, endure bizarre stress-tests, and receive dry-runs and do-overs in distant deserts. They are the subjects of sweeping sanctions, which ultimately only subvert their supply chains. And after being trafficked halfway across the world, they target and kill infantrymen who have, in many cases, never left their hometowns.

No modern weapon lives as many secret lives as the Shahed 136 drone, produced by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). The Shaheds are colloquially known as ‘suicide drones,’ partially because their name means “martyr” in Persian. These drones are launched from mobile truck-mounted racks, travel long distances, loiter over their target, and then impact them warhead-first. They’re designed in Iranian polytechnic universities, tested by Iran-backed militias in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen, shipped through Central Asia, copied and mass-produced in Russia, and launched against Ukraine.

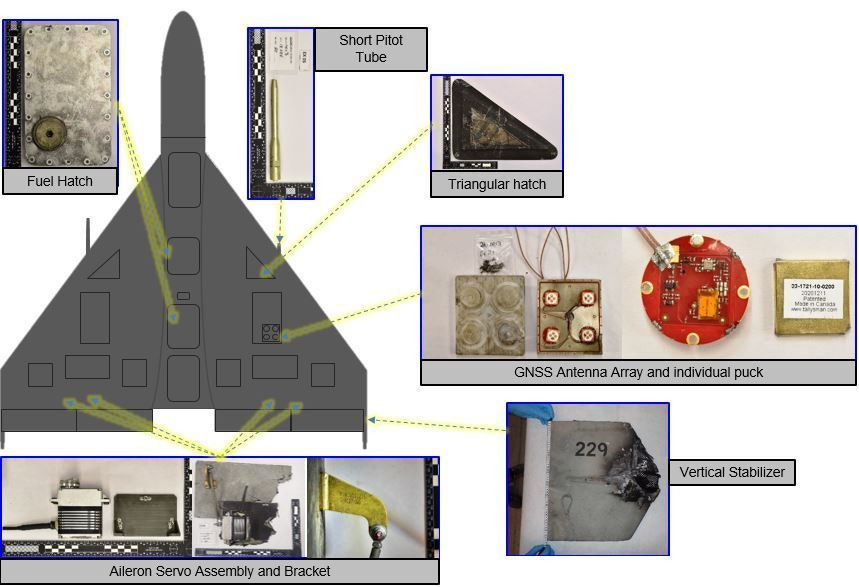

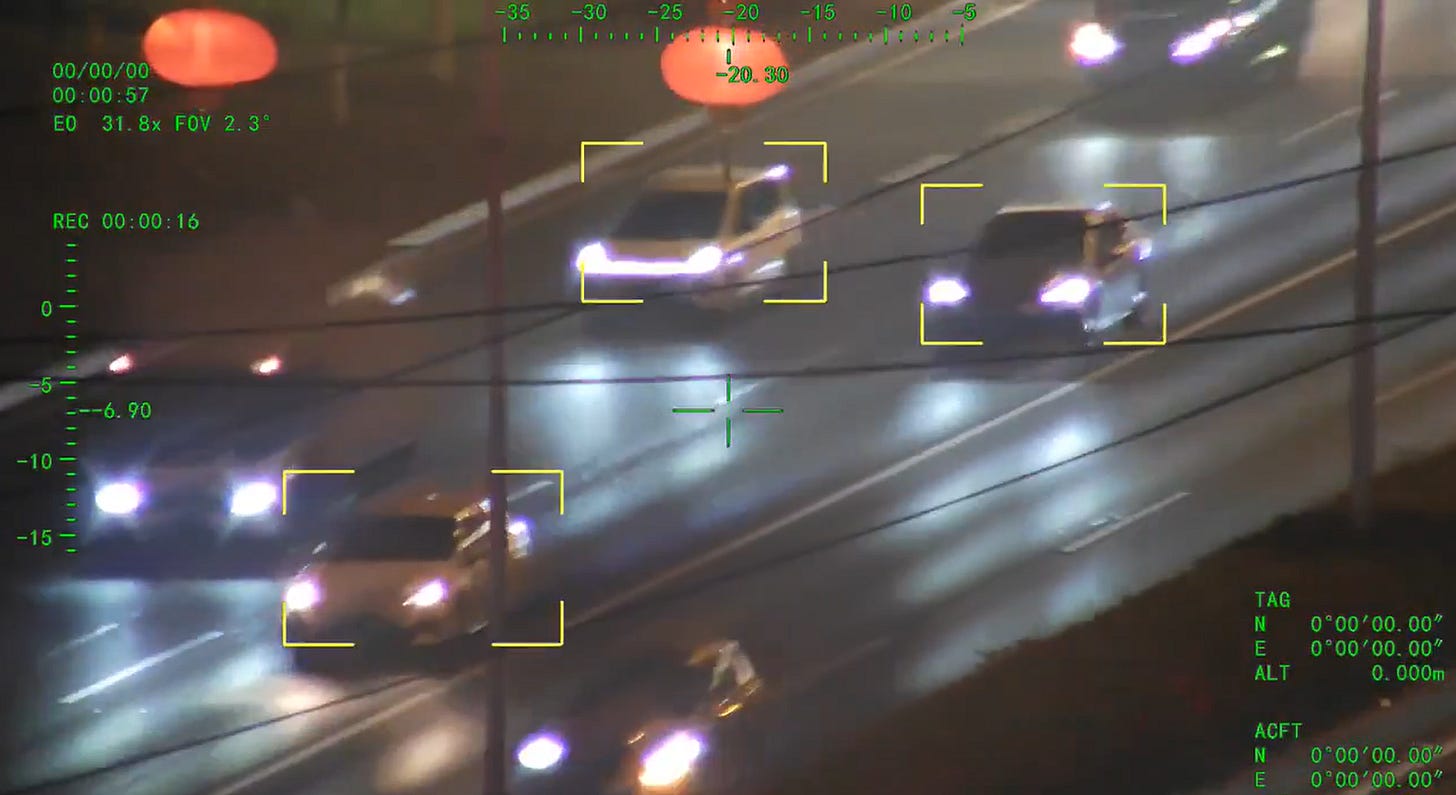

They also think. The Shaheds have an AI pilot that uses machine learning to identify the most lethal or valuable target, and then destroy it. They identify these targets with high-powered omnidirectional cameras. These AI-piloted models include top-of-the-line, American-made Nvidia chips. Target recognition is constantly being processed, as per the screencap below, taken from footage recovered from the memory card of a downed Shahed. (The footage appears to depict a highway outside a facility in China, the origin of the camera.) This means that target prioritization, when it happens, is instant. They are nothing less than a thinking bomb, and they learn through the experiences of their peers. That’s why Shahed testing by Iran-backed militias is so important: each deployment adds to the AI pilot’s shared database of recognized targets. Every Shahed launched by Shia militias outside Aleppo or Houthis in Sa’ana improves the lethality of the Shaheds raining down on Kyiv.

In this regard, all the secret lives of these ‘martyrs’ are interlinked. If nothing is done to interrupt this kill chain, autonomous Shaheds will enter a positive feedback loop of machine learning. They will become smarter faster than we can possibly respond. Defending against them would be next to impossible.

In this brief, I use an all-source approach, including geospatial imaging, social-media scraping, on-the-ground sources, and open-source shipping records, to track each stage in the lifecycle of a Shahed drone. Whenever possible, I have summarized or simplified matters that relate to the IRGC’s Quds Force, in anticipation of a future tracking project on the militias they back.

Design

All Shahed models begin their lives as ideas. They are dreamed up from first principles and adapted to lethal force. I used open-source documentation, including academic records in Farsi, to track how the IRGC turns innovation into prototypes: new designs, additions, and modifications.

The IRGC’s own Imam Hossein University is the locus of new Shahed development. It produces scholarly journals in Farsi, like the Journal of Aerospace Mechanics and the Electronic and Cyber Defense Journal. These journals publish work by professors and master’s degree students, from physics to mechanical engineering. Many of these innovations are produced by Iranian officer schools, including Iranian Army’s Imam Ali Officer University, and the Iranian Air Force’s Shahid Sattari University of Aeronautical Sciences and Technology. The ever-expanding corpus of “Shahid Literature” also includes strategic writings and use cases, which assists targeting officials in the Iranian military, and in the militaries Shaheds are sold to.

This chain of innovation provides the IRGC’s Shahed Aviation Industries Research Center with new models, which they lease to a Russian joint-stock company. The new models are then mass-produced in Russian territory. The diagram above was composed using open-source information, including sanction-enforcement records and academic records. It depicts the innovation ecosystem for Iranian drones, and the leasing agreement which mass-produces them.

Imam Hossein is also the site of initial physical testing. It’s host to the Ghadir Aerodynamics Center, which Iranian state documents identify as one of the largest and most powerful wind tunnels in the country. It has a rare combination of subsonic, transonic, and supersonic capabilities, and is a natural testing ground for new Shaheds.

Furthermore, Imam Hossein is host to a small airfield, identified by some Persian-language maps as the IRGC’s flight school. I used geospatial imagery to look at this airfield in detail, and found distinctive debris patterns near a cluster of buildings on the edge of the property.

There’s a row of light industrial buildings with pale roofs, most likely warehouses or workshops. Scattered nearby are triangular chunks from white airframes, between four and five meters wide. That’s about the same width as a Shahed. I am highly confident that some initial Shahed testing takes place at Imam Hossein university, either in the wind tunnel or on this airfield, or in both places.

But flight testing is not the end. Before being rolled out to the Russian market, new Shahed models will earn their stripes on the battlefields of the Middle East.

Field Testing

The IRGC field-tests Shahed drones by providing them to Iran-backed militias, many of whom are armed and advised by the extremely secretive and lethal Quds Force. These Iran-backed forces include Shia militias in Iraq and Syria, and the Houthis in Yemen.

New Shahed models travel across their home country, from Tehran or Isfahan to an illegal or semi-legal border crossing. They may be labeled as tractor parts or machine tools. Telegram channels representing Iraqi militias claimed that some transfers take place overland near Sulaymaniyah. This smuggling is empowered and carried out by Iranian conglomerates, which illegally buy oil for the Iranian regime, shield the true nature of their smuggling activities, and fund the Iraqi militias mentioned above.

They move west across Highway 7, and soon they have reached the al-Qaim or Albu Kamal border crossing, or the illegal ‘Sikak’ military crossing. They come to rest at Deir ez-Zur, the largest city in southern Syria. Local Syrian journalists reported that Deir ez-Zur has been excavated by Iranian forces, with tunnels scattered across the city. Many Syrian social media accounts claim that Iran-backed militias store weapons, including drones, in these tunnels.

Also of note are various makeshift depots in Al Salhiyyah, a suburb of Deir ez-Zur across the Euphrates. Al Salhiyyah, home to the Quds Force’s notorious ‘Iranian Square’ depot, is also the site of the geospatial image included below. Although the sharpness of the image is less than ideal, the footage was taken very recently: just four days ago. I am somewhat confident that these are launch rails for drones, surrounded by scattered missile defense and radar equipment. The damaged perimeter walls may be the result of recent fighting between Iran-backed militias and the American-backed Syrian Defense Forces, which has a large contingent of Kurdish fighters.

Indeed, this evening, the SDF “carried out a raid campaign in the town of Al-Tayyana in the eastern Deir Ezzor countryside,” confiscating weapons systems which may have been provided by Iran. The Deir ez-Zur area was also the site of recent air-to-air warfare involving Shaheds. During Israeli strikes on the territory, a Shahed was destroyed by an air-to-air missile. Photographs of the exchange are attached below. From left to right, top to bottom: the drone flies due East, the Israeli jet follows, the jet launches an air-to-air missile, and the jet passes by the wreckage of the drone.

Though this exchange was a win for the Israeli jet, it may well contribute to long-term losses: the Shahed database now has data on air-to-air rockets. The AI pilots leading the next wave of Shaheds will access this information and account for it in their targeting. The IRGC’s aim, adding discrete bits of data to the larger system, has been fully achieved. Simply put, the drones are smarter now. The hardware itself was a martyr for that cause.

Shipment

Russian procurement officers do not often buy new products sight-unseen. Once a new Shahed model is developed, and new hardware is innovated and tested, the IRGC must transport it to Russia. The model will undergo further testing, including battlefield tests, and if it performs well it may enter mass-production under the existing lease.

I used open-source, publicly available shipping data to identify a likely shipment of Iranian drones or drone parts across the Caspian Sea. The Port Olya-2 is a Russian-flagged cargo ship. It left a port not far from Tehran about four days ago, and docked about six hours ago in Astrakhan, Russia, where it unloaded its containers.

The Port Olya-2 is owned by MG-Flot LLC, a company which is associated with Astrakhan businessman Jamaldin Emirmagomedovich Pashayev. Pashayev has been sanctioned by the United States for his material support to the Russian government, including illegal weapons shipments.

I am highly confident that unmanned aerial vehicles or the parts needed to assemble them were among its cargo. In coming months, it may face the same fate as the Port Olya-4, which was sunk by Ukrainian drone strikes. It was their first operation in the Caspian theater, and it may not be their last.

Mass-Production

If the Port Olya-2 was to continue up the Volga River, it would eventually reach Tartarstan. In this enclave, in a special economic zone, lies the beating heart of the Russian war economy. It is where the Shaheds are mass-produced.

Reuters reviewed video footage of the factories in Alabuga, owned by the joint stock company identified in the diagram I created above. The factory, located in Russia’s Tatarstan region, “invited school pupils to study at a college… once they had completed ninth grade (aged 14-15), so that they could study drone manufacturing… and then work at the factory when they [finish] college.” Indeed, Russian state administrators do not believe that the Shahed economy is going away. Rather, it’s just getting started, and entire classes of children are being reared to one day join that economy as manufacturers.

This is where it happens: Shahed mass-production. Note the six helipads, which imply frequent visits to the site, probably by military helicopter. Also of interest are the rail and road access, with wide roundabouts for shipping via semi truck. But in the end, it matters less how Shaheds cross Russia. What matters more is where they’re going.

Use

The mass-produced Shaheds are now well-traveled. Their progenitors have criss-crossed the world, from innovations in Iran to stress-tests in Syria, and shipping in Central Asia. They come to rest in occupied Crimea, at Russian launch sites.

One such site, in Cape Fiolent, on the southern tip of Crimea, was carefully prepared to protect Shaheds before they’re launched. The geospatial image below shows the same Russian military installation in Cape Fiolent, in 2021 and 2025.

I am highly confident that this is a drone-control installation. The recently added satellite dishes are designed for in-air control and communication. There are visible cable trenches and conduits, along with a row of containers, likely for signal processing and data storage. It’s wrapped in a perimeter fence, and there are raised plinths at the edges, which is consistent with the presence of generators or possibly radiofrequency shelters. In short: this is the uplink for Shaheds.

I am fairly confident that these are the trucks carrying the Shaheds. They’re parked only a few miles from the uplink site, in this clearing. These are Ural-4320s or Ural-375Ds, both of which can carry launch racks for Shaheds. The trailers attached to the backs of some of the trucks are most likely generators or batteries for the launch racks, to help propel the drones into the air. After that, the rocket ignites. Then the Shahed is off.

It may cast its shadow over the Black Sea, or over the front line in Donetsk. It may travel over the marshes near Odessa to strike a Ukrainian oil refinery, or it may plummet into a government building in Kyiv. It may kill no one, leaving a large and useless crater. Or it may scream down onto a civilian truck loaded with crates of fresh produce.

I spoke with a Ukrainian refugee about the Shaheds. She’d most recently been in the country in the early months of 2025.

“They are a part of normal life now,” she said of the drones. “They are loud, almost as loud as an airliner, and they buzz through the sky at all hours. No place is safe from them.”

In the images below, a Shahed approaches and strikes a civilian vehicle, obliterating it. The strike was just a few days ago, on October 18th.

Make no mistake: the Shahed is a weapon of total war, not tactical combat. It’s designed to hit power grid, industry, and state-institutional targets: to inflict maximum suffering on a population, and make them capitulate. But Ukraine has not quit.

As I’ve proven, these Shaheds, these martyrs, are rich with strange experiences, and live long and varied secret lives. They are the result of a carefully forged Eurasian kill chain. But their strength is also their weakness. If they can break one link in the chain beyond repair, whether in Tehran or the Caspian, the flow of drones will stop. Once Ukraine is fully armed to degrade and destroy Russio-Iranian power, the hard part won’t be getting it done. It’ll be choosing a place to start.

Excellent analysis. The AI aspect is so chillingly complex.