Four Hundred Seconds to Tel Aviv

On Stuxnet idylls, defensive developmentalism, and Tehran's sordid love affair with the atom.

“I am Gravity,” Thomas Pynchon writes in 1973’s Gravity’s Rainbow. “I am That against which the Rocket must struggle, to which the pre-historic wastes submit and are transmuted to the very substance of History.” Since its inception, the Persian nuclear program has been subject to various types of gravity: revolution, diplomatic opposition, targeted assassination. Might we sift through the substance of that history and see where it leaves us? What does the history of Iran and the atom tell us about our future?

The Origins of Modern Political Order in Iran

We open in 1925, at the advent of Iranian defensive developmentalism. Threatened by the Bolsheviks to the North and the Ottoman Empire in the Caucasus to the West, the ailing Qajar dynasty was internally overthrown by Reza Khan. Within a few weeks, he named himself Reza Shah Pahlavi (literal translation: Reza “God-King” Pahlavi) and began to aggressively modernize the country. Railroads and water infrastructure were developed into rural zones at an exceptionally rapid clip; a small cloister of monarchistic governors bloomed into a large and lavish bureaucracy. The predecessors to the notorious S.A.V.A.K. were established to suppress dissent in the core of the country. The Pahlavi dynasty was born.

Unsurprisingly, this caught the eye of Great Britain, which appreciated his secularization and rapid development, which recalled Türkiye’s Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Determined not to alienate another secular statesman in the Middle East (see the Chanak crisis, when Churchill nearly went to war with Atatürk) the British wished to court R.S.P., with minimal success. Instead, Pahlavi played the gracious host to Nazi scientists as early as 1939, in exchange for ideological resources like the propagandistic German (pseudo-)Scientific Library to Iran. Ties deepened; a joint base was established. Suddenly, Nazi battalions were within striking range of the Soviets. In response, Britain and the USSR elected to topple Reza Shah. Armored columns divided Iran and crushed the Shah’s forces. The conquering nations took full control of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, exacting a massive profit over the course of the war. R.S.P.’s reign was officially over.

In order to develop the illusion of Iranian sovereignty, the Allies installed R.S.P.’s son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, into power. M.R.P. was a generally weak ruler, under the thumb of the Allies, oil interests, and his own parliament. The peace, however, held. WWII ended. We officially enter the realm of post-war parapolitics, the territory of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. It is in this context that Iran entered its years of crisis.

Years of Fire, Years of Lead

In 1946, the same year of the Bikini Atoll Tests, the Allies parted ways in Iran. In what became known as the Azerbaijan crisis, the Red Army continued to occupy Iranian territory long after they were intended to leave. Though the United States successfully persuaded the USSR to leave the territory, the consequences included the destruction of the only Kurdish state to ever gain practical power, laying the groundwork for the persecution of Kurds which continues into the modern day. There was, however, another long-term consequence of this rough exit. The weight of the nuclear tests, exerted through American pressure on Stalin’s armies, demonstrated to Iran just how powerful a nuclear showcase could be.

In 1949, not long after the end of the Berlin Blockade, Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh nationalized the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. Mossadegh was a walking paradox. He was related by blood to the deposed rulers of the Qajar Dynasty, leading the Shah to believe that he was a radical Qajarist. The West, pathologically afraid of Communism on account of recent events in Berlin and elsewhere, believed him to be a Soviet asset. The Soviets, for their part, denounced him as an American puppet. In reality, he was neither. His parliamentary record shows him to be a cunning coalition-builder, willing to fight for the rights of Iranian women when it benefited him. His nationalization of the A.I.O.C can be best interpreted as a post-ideological move: a selfishly power-seeking act that had little connection to any prevailing ideology of political economy. Iranian national sovereignty was his goal, at the cost of all other national interests. Mossadegh did not want oil power to be socialized or Westernized, he wanted it to be as Iranian as possible. And most of all, he wanted to be loved.

It worked. Mossadegh immediately became a national hero and nationalist icon. Despite gaining vast favor among Iranians, Mossadegh was despised by the West. They cut their purchases from the newly nationalized A.I.O.C. and pushed their allies to do the same. The Company’s revenue plummeted. Viewing the incipient crisis as a threat to his power and life (perhaps, in his mind, orchestrated by the Qajar-heritage Mossadegh) Mohammad Reza Pahlavi fled the country. The self-styled god-emperor had abdicated. The country was now in a state of flux.

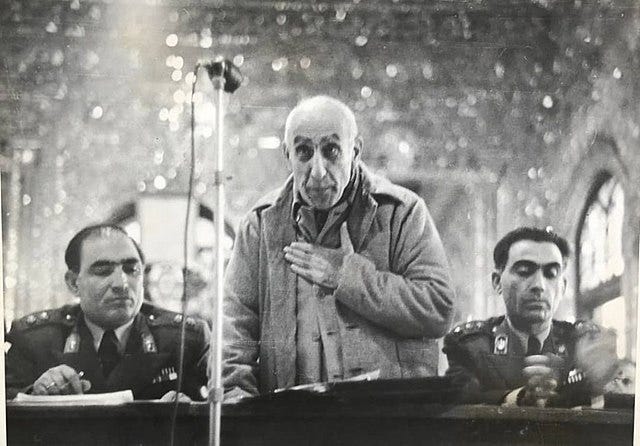

Enter Ajax, 1953. The CIA and MI6 sold Eisenhower a bold story: Mossadegh as a Soviet agent. Reluctantly, he signed the dotted line. The result was Operation Ajax. American paramilitaries armed dissatisfied loyalist officers, who marched on Mossadegh’s residence and various oil installations. Radio broadcasts transmitted readings of forged documents asserting Mossadegh’s culpability in an anti-Shah coup. Military officers, marja’ (literal translation: “sources to follow,” Shia Muslim clerics) and organized crime figures were paid off to traffic weapons and organize vast street protests with flows of money and free transportation. Mob violence began to sweep Tehran. Mossadegh called it quits; he was then rapidly tried and placed on house arrest until his death. The Shah returned from exile to a transformed country.

The coup was a short-term political victory but a total ideological loss. The average Iranian citizen quickly realized that the Shah’s return to power had been Western-engineered. CIA units remained anchored in Iran, training the Shah’s S.A.V.A.K. secret police. S.A.V.A.K. served as the Shah’s narrative-controllers, abducting and torturing dissidents with impunity. S.A.V.A.K.’s dissent-silencing practices became so unpopular that they were falsely accused of what was at the time the deadliest terrorist attack in history (but that’s not until later), an allegation that most Iranians believed. S.A.V.A.K.’s torture program was so effective that it drove democratic advocates and radical Islamists alike underground. Chief among them was a man named Khomeini, who left Iran in fear, but would return as an ayatollah.

It was at this critical juncture, a hinge point in Iranian politics, that the Shah once again engaged in defensive developmentalism. His program was known as the White Revolution, and it lasted from 1963 to 1979. It entailed rapid secularization, rapid gains in women’s rights, changes to the system of land distribution, and liberal reforms across the economy. These changes were economically alienating to the bazaar sellers who distributed basic goods, and intensified the scale and scope of urban poverty. Peasants were alienated by the neoliberal land ownership policy, while Muslim leadership was greatly disturbed by societal reforms.

The final stage of defensive developmentalism as practiced by the Shah was the first grasp at the atom. It happened under Eisenhower, as part of his ‘Atoms for Peace’ policy. The stated goal was to unleash the power of nuclear energy across the world, but there was a secondary strategic purpose: to allocate the atom to nonaligned or loosely aligned nations in order to persuade them not to consort with the Soviets. In Iran’s case, that meant American scientists on the ground, and deliveries of uranium both in its enriched and unenriched forms. MIT and the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission even collaborated to develop a nuclear research reactor in Tehran, the first of its kind. By 1967 Iran planned to build 25 nuclear reactors, with a blueprint for a fully nuclear-powered national grid, freeing up all oil reserves to be exported. Three years later, acknowledging the ease with which atoms for peace could become atoms of war, Iran joined the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The Shah made public his vision for the future: Iran as another Japan, a former Axis power turned powerful friend of the West. The seeds of revolution, however, were soon to spawn a thick mass of weeds which broke through his well-laid plans.

Falling Upwards and Rising Downwards

The early 1970s should have been Iran’s best years, but they quickly morphed into a decadent nightmare. The discovery of large oil reserves (paired with a boom in global oil demand) vastly increased the rate of cash flow into the nation. Inflation reshaped the economy, entrenching the urban poor into a state of subsistence. Basic necessities multiplied in price. Meanwhile, Tehran began to replace Beirut as the party capital of the Middle East. Diplomats from across the Muslim world rubbed shoulders with East Coast nuclear physicists and Texas oil magnates. Billions of dollars were allocated by the Shah to the purchases of American rockets and bombs. The monumental royal residences at Persepolis were twice renovated and barely used.

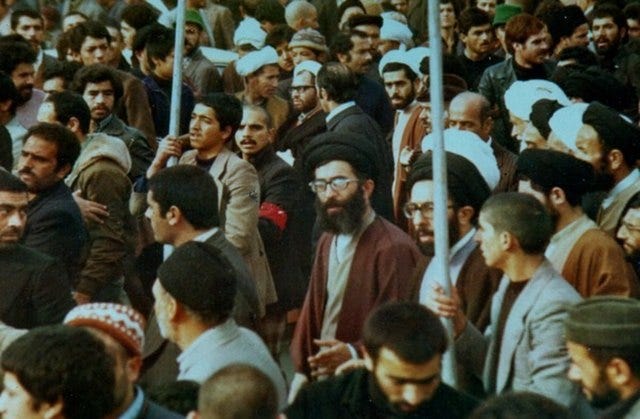

Enter the Iranian opposition. Pursued by S.A.V.A.K. into a state of European exile, they were broken, but patiently waiting for a charismatic leader to fix them. That leader came in the form of Ruhollah Khomeini, living at the time in Paris. An acquaintance of postmodernist Michel Foucault, Khomeini’s ideas were a synthesis of Salafism (Sunni fundamentalist reform) and anti-colonial, anti-Western thought. Khomeini’s lectures on this synthesis were smuggled back into Iran via samizdat cassette tape, where they spread like wildfire through the large population of alienated youths. Like the nuclear fission taking place in underground labs beneath the sands, the process of political decay quickly became unstoppable. The state began to squirm.

In such periods of political decay, political theorist Francis Fukuyama argues that a vicious cycle is all but inevitable. When legitimacy-troubled states fail to live up to expectations, distrust in the state is reinforced and validated, leading to less investment by the people into the state, leading to further failures of the state. The example of Iran, however, proves that states don’t just fail: sometimes, they actively hurt their own cause. Take, for instance, Ayandegan. A government-approved newspaper, Ayandegan repudiated Khomeini’s rising influence. Student protestors mobilized to condemn what they perceived as a grave insult. Local authorities, supported by S.A.V.A.K., opened fire on the protestors. As the 40 Days of Arbaeen (a Shia festival of mourning for Hussain ibn Ali) began, religious commemoration merged with student protests. The urban poor joined forces with the previously disbanded leftist movements and rushed into the streets. Oil workers put down their tools and went on strike, en masse, from distant oilfields to local utility plants. The country was now on fire.

1978. Iranian state institutions entered their most difficult summer since the fall of the Qajar dynasty. In August, a fire at the Rex Cinema struck a kaleidoscopic terror into the heart of the country. It was a day of body bags and contradictions: more than four hundred people burned to death in a theater with all the doors chained and padlocked. Every single fact of the case was paired with another competing fact: the cinema often showed anti-government films, but the fire broke out during a government-approved drama. The government claimed that Khomeini’s underground network of revolutionaries was responsible, but the general public placed the blame on S.A.V.A.K., who they claimed had used the fire to dispose of various revolutionary outlaws. The summer simmered and again exploded in September, when martial law was declared. The military promptly broke protests by shooting thousands and killing hundreds; the last shreds of belief in a peaceful reconciliation were tossed aside. As the year came to an end, the Shah attempted a panicked restructuring of the government, but nearly the entire civil service was on strike. There was no one to execute the new legislation. In January of 1979 he left Iran, never to return. A month later, Khomeini returned, finding himself the nation’s supreme leader.

The collective trauma of state violence rapidly coalesced into revolutionary fervor. Power players fled the country, taking permanent vacations to Switzerland and the United States. Elites moved their money offshore and foreign investment slowed. An inordinate amount of the remaining population began to support the development of an Islamic Republic, with approval supposedly polling at over 98%. The structure of the Shah’s government was erased and the constitution was rewritten. The players which had supported the White Revolution were executed. Velayat-e Faqih (literal translation: rule of the jurist) was imposed, instituting a baroque system of multilayered ‘approvals’ for elected and appointed figures. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps replaced S.A.V.A.K., though dozens of torturers and signals intelligence workers were retained. The I.R.G.C. also took possession of the American-trained nuclear scientists. The raw potential of the atom was now in the hands of the Islamic Revolution.

The First Years of the Islamic Revolutionary Government

In the South Atlantic Ocean, an American satellite spotted two flashes on the horizon. Analysts believed that the flash was a joint nuclear test by Israel and South Africa, in violation of international law. September 1979 thus represented the first indication that major powers in the Middle East and Africa would someday have access to nuclear arsenals. An Iranian nuclear weapons program was no longer an impossibility.

One month later, in the wake of the White Revolution and Islamic Revolution, defensive developmentalism would again rear its head in Iran. This time, it emerged on account of a hostage crisis and a doomed fleet of helicopters. It started in October of 1979, when the exiled Shah’s American visa was accepted by the Carter administration. Though he was seeking treatment for an aggressive cancer, the Iranian population interpreted his visit as a precursor to a re-do of Operation Ajax. Anti-American sentiment exploded; young Iranians for the first time began adopting Khomeini’s rhetoric, including such phrases as “the Great Satan” and “death to America.” The American embassy was identified, then, as the core of a pernicious Western influence which supposedly stood to push Iran into deeper chaos. After days of protests, the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line (a non-state actor) broke through the gates and seized the facility. Sixty-five American hostages were taken; thirteen of them, primarily women, were released early. The fifty-two that remained were treated to grueling interrogation, solitary confinement, and weeks of imprisonment. In America, yellow ribbons became a symbol of remembrance and hope for the fate of the hostages, evoking the later use of the yellow ribbon in the wake of the October 7th attacks and hostage-taking by Hamas. The four hundred and forty four days of confinement served to deepen and institutionalize anti-American sentiment in Iran, making combating America a primary directive of state institutions. The most disastrous moment of the hostage crisis was Operation Eagle Claw, wherein Delta Force suffered a series of mechanical failures at a remote airstrip inside Iran. A haboob, which Khomeini declared an “act of God,” obscured visibility and led to a fiery crash that killed eight soldiers. The blackened wreckage, sitting sunburned in the sand, served as a signal to Iranian leadership: America was coming for them.

As Carter’s presidency came to an end, Algerian diplomats mediated the release of the hostages, supposedly in exchange for the freeing-up of Iranian assets as well as concessions across the Islamic world. In reality, the Iranian government was primarily motivated by the rise of Ronald Reagan, who projected a vision of military strength and offered a series of public and covert opportunities to the Iranian state and military. The hostages were released just minutes after his inauguration.

The following year, Iran became embroiled in an eight-year conflict which taught them two apocalyptic lessons about defensive developmentalism. That conflict was the Iran-Iraq war, sparked by various events on the border between the two nations, including Ayatollah-backed Shia uprisings in Iraq and Saddam Hussein’s expansionist treatment of shared waterways. Iraq’s forces were pushed back on the defensive, where the conflict stalled into bloody foot-by-foot trench warfare and human wave attacks. Worried about escalation of Iranian power, the United States supplied chemical weapons like mustard gas to Saddam Hussein. This open secret, upon reaching Khomeini, taught him a major wartime lesson about defensive developmentalism: America was willing to escalate the grade of weaponry in order to contain Iran. Iran responded in kind, releasing Tabun and Sarin onto the battlefield. For the final four years of the war, the United States Navy regularly smashed through Iranian naval supply lines in what became known as the ‘Tanker War.’ Not long before the end of the war, the USS Vincennes unintentionally shot down Iran Air Flight 655. Through the war and into the stalemate, American leadership viewed their position as one of nonalignment and power-balancing, while Iran viewed them as a discrete combatant pulling the strings of the enemy leadership.

However, as noted above, the war held for Iran a second lesson about defensive developmentalism. If American support of Saddam was an open secret, then this second lesson was a closed secret inside an open one. In the West, we know it as the Iran-Contras Affair. In order to raise money for Latin American anticommunist militants who were condemned by Congress, Reagan’s executive branch ultra-covertly sold arms to Iran. Amid the war with Iraq, the Ayatollah received TOW anti-tank missiles, Hawk anti-aircraft systems, and spare parts for tanks. These were advanced targeted munitions, a flagrant violation of the arms embargo against the country. The lesson learned by Iran was that covert exchanges of money led to fruitful results. The Iran-Contras Affair gave Iran the network required to launder money, trick and coerce trade inspectors, and double-deal outside of international law. These dirty tricks, taught in the name of global peace, would become the foundation of the nuclear program that the Ayatollah had always wanted.

Multiple Deaths and the Conqueror Worm

In 1989, Ayatollah Khomeini suffered five heart attacks in a single day. He died that night, thus ending the first Islamic Revolutionary government of Iran. He was succeeded by the similarly named Khamenei, though they have many practical differences in government. The first Ayatollah had a cult following and was a Sufi, a gnostic and ascetic devotee of Islam who assigned a mystical character to the religion. His successor, Khamenei, who remains in power today, is far more practical. Khamenei transformed the Iranian state’s foreign policy into a complex web of state and non-state actors from the Levant to Central Asia, working towards the degradation of American and Israeli interests. Khamenei’s government has also persecuted Sufis and other mystical practitioners of Islam, marking a substantial departure from his predecessor’s religious views. Perhaps it is no surprise, then, that Khamenei’s Iran is regularly rocked by protests and crises of legitimacy, consistently put down by force. And there is, as you will see, a profound symmetry at play between this political decay and the rise of nuclear Iran.

Not long after the death of the First Ayatollah, the world was reshaped by the collapse of the USSR. Hundreds of tons of nuclear material were smuggled out of the country and into Central Asia, where it vanished into the wild steppes (read: black markets) of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. The new Ayatollah approached various nations in the early 1990s about the possibility of nuclear acquisition, chief among them China, the Russian Federation, and Pakistan. Pacts of cooperation were signed with the first two and then dropped on account of American pressure; though limited cooperation may still have occurred, little evidence of it remains. A secret Pakistani network was the real means of support for Iran, supplying them with raw nuclear material. Late that decade, the Amad Plan was approved, ordering the development of a five-weapon rocket arsenal over five years. Everything was falling into place, except one detail: despite access to nuclear material in its raw form, the I.R.G.C. could not get their hands on anywhere near enough refined uranium or plutonium. This race for refined material became the defining feature of Iranian nuclear politics for decades, up to the present day.

The next development came in 2002, when the People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran, a former armed dissident group, arrived in Washington, D.C. with a detail-heavy slideshow. They revealed the existence of Iranian nuclear facilities at Natanz and Arak, already advancing towards the development of a nuclear arsenal. The International Atomic Energy Agency awakened from their slumber to confirm that the allegations held weight. With extreme international pressure frightening Iran into submission, a cessation agreement was reached with the European Union.

The pause, however, did not hold. Two years after the agreement, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won the presidency after being approved by the Supreme Leader. Ahmadinejad was an Islamist hardliner, an extreme anti-Western personality, and he restarted development almost immediately. The nation withdrew its earlier nuclear security commitments. Development rapidly progressed again, even in the face of crushing global sanctions. It wasn’t the thunderstorm of sanctions, but a tiny worm that stopped the nuclear program in its tracks.

The Stuxnet worm was the product of Operation Olympic Games, the result of collaboration between the NSA and Mossad. At an undisclosed location in the Negev desert, Israel used satellite footage and defector testimony to create a functioning full-scale replica of the Iranian nuclear laboratories. Since the program ran on Windows, the worm was able to exploit simple vulnerabilities: nodes called Siemens PLCs (programmable logic controllers) that control the rate at which centrifuges spin. Stuxnet, then, had two goals: first, to rapidly replicate itself and spread throughout a network, and second, to physically disable the system. The worm simply raised the speed of rotation to inadvisable levels and waited for the damage to appear. More than a thousand centrifuges were thus permanently disabled. A year after the conclusion of the operation, in 2010, researchers discovered the worm; two years later, its existence was revealed in a New York Times headline. Iran hit back, targeting American and Israeli businesses, as well as Saudi Aramco and other Western-aligned Arab oil companies. Undeterred, the Ayatollah was not destroyed by Stuxnet, though it did manage to slow him down.

The same year Stuxnet was released, Benjamin Netanyahu began his second term as the Prime Minister of Israel. Netanyahu’s consistent position is that Iranian nuclear weapons represent an existential threat to Israel, one which must be stopped no matter the implications for international security. Thus, Mossad began a campaign of targeted assassination. In the heart of Tehran, five nuclear scientists were assassinated by a combination of car bombs and motorcycle-driving gunmen. The program of targeted assassination successfully brought Iran back to the table for the J.C.P.O.A., one of the most notorious gambits in all of nuclear history.

The Plan and its Consequences

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or J.C.P.O.A., was an Obama-era policy designed to contain Iran by offering them a major concession: the lifting of those total sanctions mentioned above. In exchange, Iran had to once again commit to Atoms for Peace. They would be under constant monitoring by the International Atomic Energy Agency, who would verify that they were enriching only small amounts of uranium in certain archaic types of centrifuges, only for the purposes of nuclear energy. After months of grueling negotiation in Vienna, billions in financial assets (including, notoriously, hundreds of pallets of unmarked cash) were rapidly unfrozen. However, the Iranian economy stumbled, expecting Western investment that never came. Less than two years after the Plan was instituted, in 2018, Trump pulled out of it, claiming that it was a bad deal. His rationale stemmed primarily from the Plan’s ‘sunset clauses,’ which predetermined the time at which the terms of the deal would no longer apply. It should be noted that he also expressed realpolitik concerns about Iran’s rising support of Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen, both recipients (via the I.R.G.C.) of major weapons shipments. As the Plan collapsed, the State Department resumed total sanctions against Iran. Almost immediately, nuclear enrichment resumed. Iran was again moving towards the development of a nuclear arsenal.

Here’s the billion dollar question: was the J.C.P.O.A. effective? Well, it depends who you ask. In terms of containing nuclear weapons proliferation, it was rather effective. The International Atomic Energy Agency never found any evidence to suggest that extraneous enrichment was happening, or that Iran was extracting nuclear material outside the terms of the deal. Access to facilities was nearly total, a huge expansion compared to the non-Plan status quo. For a few years, the I.A.E.A. could go wherever they wanted, and see whatever they wanted. Facilities consistently passed inspections of the snap and scheduled variety, and I.A.E.A. employees themselves regularly passed anti-corruption probes. In terms of containing baseline nuclear proliferation, it was of course ineffective: deal or no deal, Iran was always going to attempt to enrich uranium for ostensibly peaceful purposes. The value of the Plan was not that it stopped enrichment but allowed the West to contain it to a reasonable level and monitor it as it occurred. However, the Plan can be considered a failure in other fields. Iran’s economy never reached predicted or promised levels; Western companies never considered Tehran a home for reasonable and safe investment. The I.R.G.C. never reduced global interactions with armed groups, and Iran remained a state sponsor of terror. Bonds with Syria’s Assad regime were strengthened rather than weakened, frustrating the State Department. In summation, assessing the Plan is less a question of ‘good or no good,’ and more a matter of ‘good here, bad there.’ The Plan’s consequences are of vastly different orders and resist rational evaluation. You are welcome to try to compare a Smyrna fig to a Jericho date, even eat a bushel of the fruits, but don’t expect to get anything out of it but a stomachache.

Pen and Paper Failed, or, Falling Back to Bullets

Two years after the breakdown of the Deal, the program of targeted assassination resumed. On the 3rd of January 2020, General Qasem Soleimani was assassinated by a rocket fired from a Predator drone. He was the leader of the I.R.G.C.’s Quds Force, their major anti-Israel battalion, which organizes the flow of money, weapons, and combat plans to groups like Hezbollah and the Houthis. On the 5th of January, Iran officially broke the last remaining tenet of the J.C.P.O.A. and declared their intent to acquire more nuclear centrifuges. On the 8th of January, they launched Operation Martyr Solemani, firing twelve ballistic missiles at American positions in Iraq. One hundred and ten American servicemen suffered traumatic brain injuries as a result of the attack.

The same afternoon, the I.R.G.C. shot down Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, echoing the shootdown of Iran Air Flight 655. Both Iran and America then stood down, preserving the region from the risk of a larger conflagration. Further investigation revealed that the plane had been misidentified as an American cruise missile, sparking another wave of the long-term protests which continue to shake the foundations of the Iranian state.

The Raketen-Stadt and the End of History

Today, the Ayatollah rules a deeply unsteady state which nears collapse. Political decay has hollowed out most economic and governmental institutions within the nation. The average Iranian is politically disenfranchised and hates both the West and their leaders. Everyday Iranians no longer trust their government or their military to defend and protect them. They grow tired of the ‘morality police’ and the persecution of Sufi figures like Noor Ali Tabandeh. The Assad regime has been toppled in Syria. Iran is unlikely to ever recover the power it invested in Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis. And Trump and Netanyahu speak openly of airstrikes against Iran’s nuclear facilities if a new nuclear deal is not reached. This morning, Al Jazeera reported that Iran will for the first time come to the table for direct nuclear negotiation with the United States of America. The talks will occur in Moscow. If Trump somehow manages to extract major concessions from the Ayatollah, there is a nonzero chance that the resultant unrest could topple the Iranian regime.

It increasingly appears that the Ayatollah’s last hope to unite his people is a catastrophic total war against Israel and the United States. Last year’s two-hundred missile launch against Tel Aviv and recent escalations in the Red Sea imply that he may be courting this possibility. His use of propaganda would certainly indicate this. “Only four hundred seconds to Tel Aviv,” one such poster goes, referring to the Fattah-1 hypersonic rocket. It’s unclear whether or not the Israeli Iron Dome would be able to withstand a hypersonic rocket, especially if loaded with cluster munitions or a nuclear warhead with maneuverable reentry capabilities. But perhaps clarity isn’t the point.

Maybe the point is theatrics; as Pynchon defines them. War-theater as system maintenance, test launches into the ocean as a way of proving that the rockets can get to Tel Aviv so that they never actually have to. And maybe Fukuyama’s thesis about the End of History and political order isn’t right. Maybe the Iranian regime is using war theater as a form of long-term stability, keeping the people quiet by making promises about the destruction of Israel. Finally, whether or not Iran continues to practice defensive developmentalism is a matter of contention. Some might argue that the American nuclear talks are a desperate re-strategization in order to keep the practice alive. Others would argue that martyrdom has become the point, and developing a nuclear program is a guaranteed and tested way of threatening the West and forcing us to come to the table. To me, it seems now that Iran is simply buying time, fighting against Pynchon’s notion of historical Gravity. “The System may or may not understand that it's only buying time,” he says of the Raketen-Stadt in Gravity’s Rainbow. “And that time is an artificial resource to begin with, of no value to anyone or anything but the System, which must sooner or later crash to its death… dragging with it innocent souls all along the chain of life. Living inside the System is like riding across the country in a bus driven by a maniac bent on suicide… though he's amiable enough, keeps cracking jokes back through the loudspeaker…”

Pen & Paper reference 🖋️📄🔫💣